In recent years, trauma has become the lens through which an extraordinary number of people narrate their lives. We are in an era where personal pain is not only shared but often monetised, aestheticised, and algorithmically rewarded. This phenomenon—where trauma becomes currency—is what I call the Trauma Industrial Complex.

The phrase echoes the “military-industrial complex,” drawing attention to a similar entanglement of institutions, incentives, and ideologies. But instead of weapons and warfare, the Trauma Industrial Complex trades in personal pain. It thrives on a market where suffering sells—on social media, in memoirs, on stage, in wellness spaces, and even in policymaking.

This isn’t a critique of people sharing difficult experiences. Speaking about trauma can be powerful and freeing. It can form solidarity, shift stigma, and catalyse healing. But in a digital culture that rewards virality, confessional storytelling is often shaped not by personal need but by external pressures: what platforms promote, what audiences crave, what funders support. This is where storytelling becomes performance—and pain becomes product.

One of the paradoxes at the heart of the Trauma Industrial Complex is that it appears to empower even as it exploits. Survivors are given platforms, but often only on the condition that they disclose, dramatise, and remain fixed in a traumatic identity. The demand is not for complexity or contradiction but for digestible narratives of suffering that fit existing templates—templates that flatten experience in the name of “authenticity.”

The system is especially seductive in sectors like media, the arts, and activism, where funding and attention increasingly flow toward what can be marketed as “lived experience.” This leads to a strange situation in which some people feel pressured to disclose trauma they haven’t fully processed, or to embellish stories to meet the expectations of funders, bookers, or algorithms. In a culture of constant self-branding, trauma becomes part of the pitch.

This is not just an issue of personal ethics—it’s structural. The Trauma Industrial Complex emerges from a society that simultaneously neglects mental health infrastructure and turns suffering into spectacle. It is the result of neoliberal atomisation, where the only recognised authority is the self, and the only recognised truth is what’s felt. In such a climate, pain is one of the few things that confers moral legitimacy.

The Trauma Industrial Complex doesn’t care if you get better. In fact, healing may disrupt the narrative. Recovery lacks spectacle; it is inconsistent, often invisible, and rarely monetisable. The system is not designed for people to move on, but to stay in place—preferably on camera, preferably oversharing.

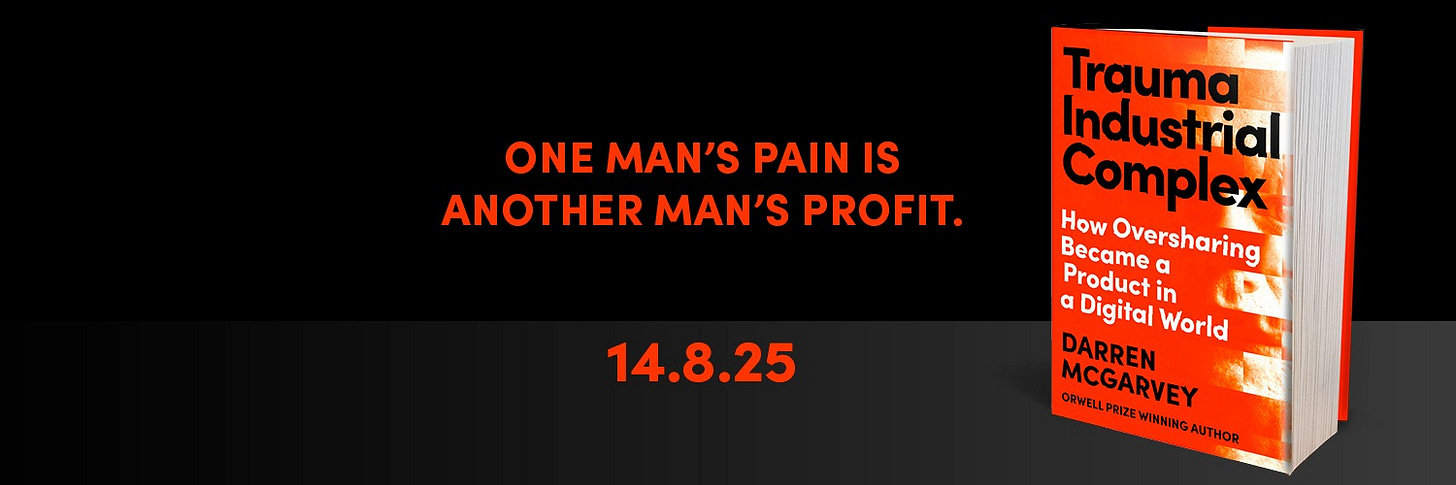

If this resonates, my forthcoming book Trauma Industrial Complex: How Oversharing Became a Product in a Digital World digs deeper into the rise of confessional culture, the economics of “lived experience,” and what happens when stories of pain become public property. It challenges the systems that reward trauma performances—and asks what more ethical, private, or resistant forms of storytelling might look like.

You can preorder the book now and book tickets to the live show, premiering at the Edinburgh Fringe, via the links below. I’d love to see you there

.

Very excited to see you’ve another book coming out man. Grew up govanhill and but went to hillpark and poverty safari was a big deal in my house me my mum and my sister all tanked through it, buzzing to see what you’ve been working on.